Welcome to Part 3 of a design diary series about my tabletop role-playing game Brave the Dreamer. If you haven’t already, you can read Part 1 and Part 2!

One goal I hope to achieve with this design diary series is to show how something that looks like one person’s creation is actually the result of access, resources, community, and support. In short, it’s far from an individual effort, and nowhere is that clearer than in playtest.

When I finished the first draft of Brave the Dreamer, I was walking on air. I’d created the best game I could possibly make, in a week no less, and I was for once confident my reach had not exceeded my grasp.

The first group1 playtest was a big serving of humble pie. Yes, I had hit pretty close to the mark, and that was validated by my playtesters and felt great. But if I was 80% of the way there, I wasn’t prepared for how deeply unmoored I’d feel around the last 20%. I was overwhelmed with all the possible paths I could take to improve the game.

What helped me most in that moment was something a random YouTuber said in this introductory video about playing the xaphoon from 14 years ago:

In English we say “play music,” not “work music.” So if you get frustrated, just relax, take a break, do something you enjoy, and come back to it later when you’re in a good mood.

Thanks, xaphman1!

Coming back to creative projects when they feel like exploration, curiosity, and play is a topic for a whole other post. For now I’ll just say that regardless of what kind of art I’m working on or where I am in the process, finding ways to engage that don’t feel like work is the only thing that has helped me maintain any sort of consistent motivation.

That said, let’s talk about the playtest process for Brave the Dreamer.

Where I Got Feedback

I’ve already mentioned that Brave the Dreamer was created for the (No) Strings Attached Game Jam. Unsurprisingly, joining a game jam was a great motivator! While I had been aware of video game jams like Ludum Dare or the annual One-Page RPG Jam, I’d never participated in one before. Fortunately, because this was a small jam among a close-knit group of friends/game designers in a dedicated Discord discussion space, it felt small and private enough to post WIPs and exchange feedback.

Once I had the first draft of Brave the Dreamer together in a Google Doc, I posted it in the game jam space, as well as a few other small public Discord servers, mostly indie-TTRPG-focused spaces that happened to have game design channels. I also sent it to a couple individual peeps.

The main benefits of doing this were:

It helped cement for myself that I was doing the thing—I made a game!

Folks shared some incredibly enthusiastic and kind words, and their excitement was encouraging.

It led to something I regard as a personal creative milestone:

People talking about my WIP, without me, after I posted it in all of like, three places! /giddy

I did get some constructive feedback from sharing the draft document around, but only a small amount, and nothing that would substitute for actual playtesting. So, over the next several weeks, I lined up a number of online and in-person playtests. I invited friends with and without TTRPG experience to play my game, and I also hosted playtests at a local TTRPG meetup and at Go Play NW, an indie TTRPG convention in Seattle.2

Interestingly, I found meetup/convention play to be categorically different than friend-group play. Although convention players were generally coming in with TTRPG experience or strong feelings about games, they were more likely to be strangers to each other, and this affected gameplay in ways I didn’t expect. Specifically, although my convention players were individually bursting with creative ideas, the story failed to cohere in a way that had not happened with the other playtests. Exactly what was missing was not obvious, but I hypothesized a couple different fixes, such as better establishment of bonds between characters or better alignment around the Dream up top, which I tested out in later games.3

In general, I had a really fun time playtesting because each game felt like its own little psychological puzzle or UX experiment. Even though I didn’t implement a particularly structured process for gathering feedback, engaging with players’ thoughts and feelings after the game was rewarding in its own right.

After five playtests (four group games that I facilitated and one friend’s solo playthrough), throughout which I was making iterative changes to the game, I decided Brave the Dreamer was ready for release. In part this was due to advice I received from Ash, one of my train-mates, that it was okay to put something out in the world that I wasn’t sure about, to trust that my design instincts would improve with time, and to return to projects later instead of spinning my wheels now. But I also felt pretty confident about the shape Brave the Dreamer was in, and only moreso after the improvements from playtest.

Navigating Critique

Although I had never made a game before this, and therefore had never received feedback on a game before this, I had participated extensively in giving/receiving writing critiques, and it seems to me there are more similarities than differences in the feedback process across these two creative domains (and probably others).

Mary Robinette Kowal, a prominent SFF author, has written about a symptom/diagnosis/prescription paradigm to help guide manuscript critiques:

Manuscript critique is like a clinical trial. Focus on your symptoms. Don't try to diagnose or prescribe unless the writer asks you to. pic.twitter.com/Kg2M2WcJ9V

— Mary Robinette Kowal (@MaryRobinette) June 3, 2017

It’s been my experience that people giving feedback on creative work are often quick to offer diagnosis and/or prescription if not prompted otherwise. For example, with Brave the Dreamer, one playtester said they felt the game was too linear during the intermissions, and they suggested having players randomly draw one of three cards with different paths forward. Regardless of the merits of this suggestion, its format is diagnosis/prescription, not symptom. And while I was grateful for the feedback, it was clear to me that if I accepted the suggestion, it would push the game in a direction I didn’t want. Keeping the symptom/diagnosis/prescription paradigm in mind helped me determine that boundary.

Another useful resource, though one I was unaware of until just recently, is this guide to getting feedback on games by Derek Yu (creator of Spelunky). Most interestingly, Yu makes a distinction between “sympathetic” feedback (from people who have strong ties to you) and “unsympathetic” feedback (which is more likely to represent the general public). I came to this article via eieio’s post on “Questions to ask when I don’t want to work,” which also tackles similar topics and resonated with me.

Tough decisions

Here are a few more examples of feedback decisions I found tough to process, and how I handled them.

1) Issue: As mentioned in earlier posts in this series, I received the suggestion to use a street magic-style word cloud from an early playtester. Though I thought this idea could help, I wasn’t sold on it because defining the Dream via a flexible, open-ended question seemed fine. However, additional playtests clearly showed that this open-endedness created more struggle than ease.

My takeaway: When in doubt, literally just playtest more. Test for the desired outcome and treat every playtest as an opportunity to gather data.

2) Issue: Early playtesters voiced a desire for more connection between their characters, which I held off on addressing until after the convention game mentioned earlier. Even after the changes, though, some players still wanted more connection/character relationships in various forms. After reflecting on it, I concluded I’d offered enough structure around this, and that offering more would take away from the feeling of fragmentation that came from the characters breaking off into their individual journeys. Brave the Dreamer can be a lonely-feeling game, and I suspected the request for more character connection was a reflection of that. At the same time, I had seen in other playtests that the game could be hopeful and relationship-oriented if the table wanted it to be.

My takeaway: The diagnosis may have more to do with the table psychology than the game mechanics, and offering better safety tools may be a more effective prescription than changing the game.

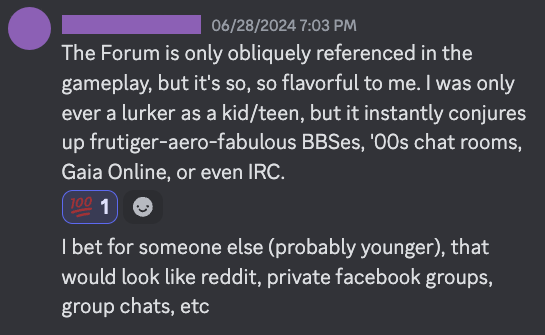

3) Issue: In Act One of Brave the Dreamer, most of the prompts were about the Dream, with only a few about the Forum. Yet I had at least two data points of people having immediate, heartfelt reactions to the latter. Although I considered tilting the prompts in favor of the Forum, I ultimately decided it received enough flavor from the Opening text and the use of screen names. I liked that people were enthusiastic about the Forum, but I suspected that excitement would bubble up regardless of whether I included more prompts. And some of the character-connection moments I’d added in response to the other feedback ended up doing double duty by bringing the Forum back around as a story thread, too.

My takeaway: Other people’s excitement doesn’t have to be my excitement, but it’s a nice bonus if changes I’m already making also give people something they’re stoked about.

4) Issue: Some players had trouble keeping track of what was happening with each of the characters. At one point, I made a half-page character sheet folks could take notes on, which seemed to help but might also have created pressure to write. Ultimately, because I was envisioning Brave the Dreamer as a card game in a box, I oriented towards the constraints of that format (which would not easily have allowed for a character sheet) and allowed the constraints to guide my design decisions—for example, explicitly instructing that players should keep their prompt cards in front of them after answering.

My takeaway: Design for the ideal vision, but if the vision is murky, start with constraints instead.

And a final, ultimate takeaway: I might not have gotten it perfect, and that’s okay. If I can just remember it’s all “play music” and not “work music,” I’ll be fine.

More to Come

This is the third entry in a series of design diaries:

Part 3: Playing well with others

In the next entry, I’ll talk about designing for production, and making pretty cards! In the meantime, you can check out Brave the Dreamer below:

-

I say “group” because technically the first playtest was, to my surprise and delight, a friend’s solo playthrough of the Google doc that I’d shared for review. ↩

-

Taking the train up to Seattle with some of the designers I’d been jamming with online was also a lovely opportunity to pick each other’s brains in person—Amtrak delays and other snafus notwithstanding. ↩

-

It was also in this game that a playtester helpfully introduced me to the concept of “endowment” from improv. ↩